Friction Factory:

Draining Desire

–

Loena Visser

Draining Desire

–

Loena Visser

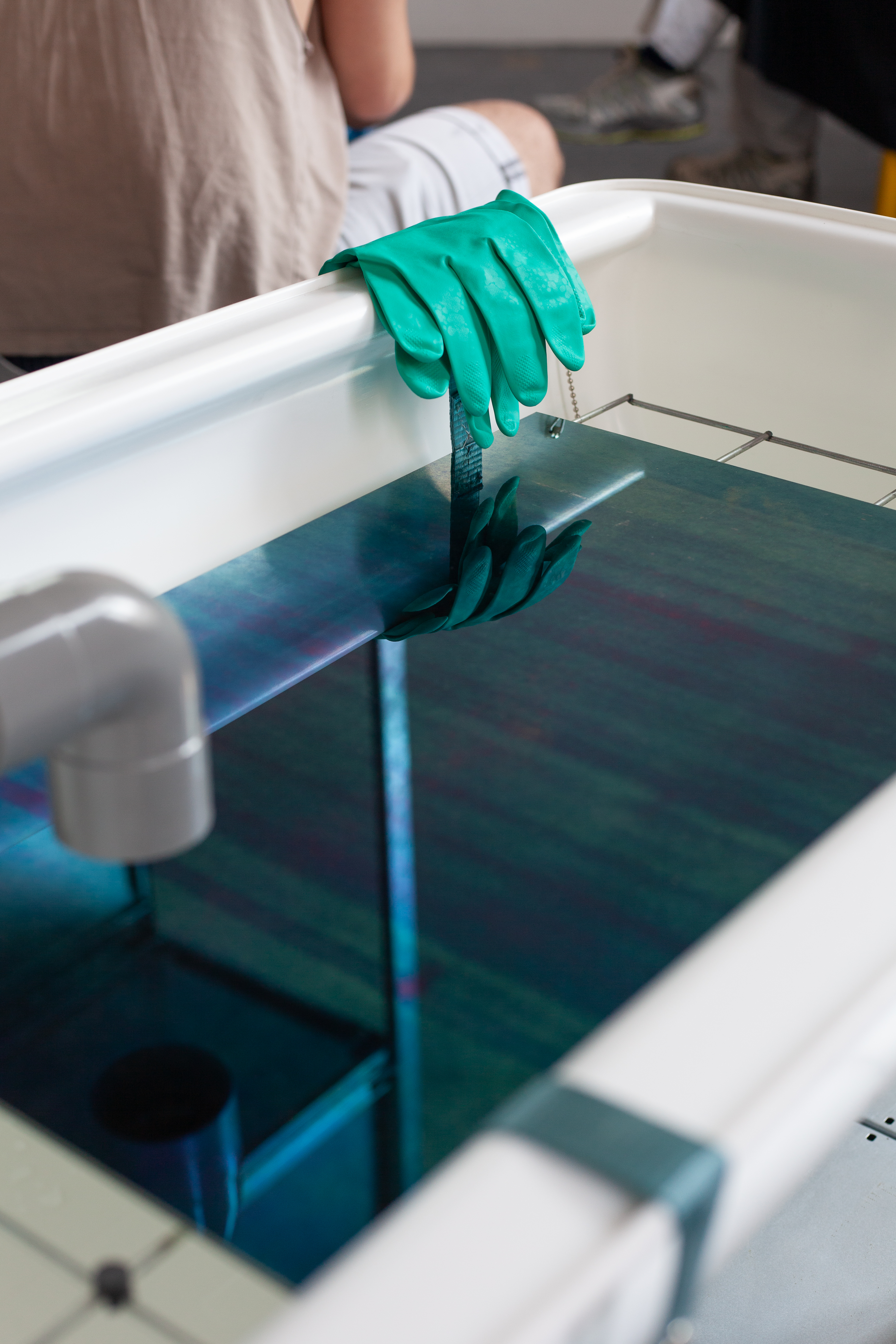

Friction Factory: Draining Desire is an installation that explores the conflicting interplay between beauty standards and their invisible toxicity. Departing from research into hair bleaching, a speculative production line is designed and attached to a hairdresser’s sink, interfering with the unseen paths of flushed-away chemicals. Inside the ‘factory’, mirrors undergo transformations caused by chemical products such as bleaching agents, permanent hair dyes, perm solutions, and hair straighteners.

![]()

The mirrors experience fast oxidation due to the corrosive power of these chemicals, gradually revealing gaps and imperfections. These marks reflect the uncertainty and limited understanding surrounding such single-use chemical cosmetics, highlighting our inability to fully comprehend their consequences. With this project, I aim to hold up a mirror – quite literally – to confront consumers, cosmetic companies, and designers with these socially constructed and industrially enforced frictions.

![]()

![]() Oxidised mirror sample

Oxidised mirror sample

Personal experience of hair bleaching and its subsequent negative consequences, such as headaches and hair loss, served as a starting point for the project, encouraging me to look further into hair bleach’s hidden impacts. Focusing specifically on the small scale of hair allowed me to uncover larger issues in the cosmetics industry, such as the availability of products that do not meet safety specifications, the prevalence of misleading ‘sustainable’ products containing lesser-known substitute ingredients with similar harmful effects, and the inconsistent regulatory systems that allow companies to exploit legal loopholes. Through my research, I gained an understanding of the profound significance of transparency, particularly concerning chemical substances, as well as learning from the concept of ‘slow violence’, articulated by Rob Nixon as ‘[…] a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.’[1] The full human and environmental impact of toxic chemicals, such as those used to meet our beauty standards, remains unclear and concealed.

[1] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2011).

![]()

![]() Process images Friction Factory

Process images Friction Factory

![Illustrations depicting investigations into the socio-political, industrial, human and environmental impact of hair bleach.]()

Social norms, perpetuated by popular culture, have normalised the production and use of harmful substances within the beauty industry. However, as our chemicals appear to evaporate into thin air, seep into the ground, or effortlessly flow down the drain, the direct consequences of our actions are vanishing alongside them. Instead of continuing to uphold these invisible structures, I believe it is crucial to utilise design as a means to evaluate and re-envision more durable alternative systems.

In addition to my highly practical BA in Industrial Design, this master's programme expanded my critical thinking skills, enabling me to zoom out and analyse complex concepts from a more abstract and conceptual design perspective. This critical eye was also the reason I faced some design struggles over the last two years, questioning my own passion for materiality and aesthetics as a designer. I have experienced feelings of guilt regarding my desire to create new things when the world is already saturated with objects. However, through this project I learned how to use these dilemmas as fuel to position myself meaningfully as a practitioner within the field, acknowledging the ambiguity and complexity of design’s impact. I am driven to continue experimenting with materials and techniques to address complex problematic processes within the field of industrial design.

The mirrors experience fast oxidation due to the corrosive power of these chemicals, gradually revealing gaps and imperfections. These marks reflect the uncertainty and limited understanding surrounding such single-use chemical cosmetics, highlighting our inability to fully comprehend their consequences. With this project, I aim to hold up a mirror – quite literally – to confront consumers, cosmetic companies, and designers with these socially constructed and industrially enforced frictions.

Personal experience of hair bleaching and its subsequent negative consequences, such as headaches and hair loss, served as a starting point for the project, encouraging me to look further into hair bleach’s hidden impacts. Focusing specifically on the small scale of hair allowed me to uncover larger issues in the cosmetics industry, such as the availability of products that do not meet safety specifications, the prevalence of misleading ‘sustainable’ products containing lesser-known substitute ingredients with similar harmful effects, and the inconsistent regulatory systems that allow companies to exploit legal loopholes. Through my research, I gained an understanding of the profound significance of transparency, particularly concerning chemical substances, as well as learning from the concept of ‘slow violence’, articulated by Rob Nixon as ‘[…] a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.’[1] The full human and environmental impact of toxic chemicals, such as those used to meet our beauty standards, remains unclear and concealed.

[1] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2011).

Social norms, perpetuated by popular culture, have normalised the production and use of harmful substances within the beauty industry. However, as our chemicals appear to evaporate into thin air, seep into the ground, or effortlessly flow down the drain, the direct consequences of our actions are vanishing alongside them. Instead of continuing to uphold these invisible structures, I believe it is crucial to utilise design as a means to evaluate and re-envision more durable alternative systems.

In addition to my highly practical BA in Industrial Design, this master's programme expanded my critical thinking skills, enabling me to zoom out and analyse complex concepts from a more abstract and conceptual design perspective. This critical eye was also the reason I faced some design struggles over the last two years, questioning my own passion for materiality and aesthetics as a designer. I have experienced feelings of guilt regarding my desire to create new things when the world is already saturated with objects. However, through this project I learned how to use these dilemmas as fuel to position myself meaningfully as a practitioner within the field, acknowledging the ambiguity and complexity of design’s impact. I am driven to continue experimenting with materials and techniques to address complex problematic processes within the field of industrial design.